A New Reading List for New Delhi

Every city inspires its own literatures, and Delhi is perhaps the most prolific of these when it comes to Indian metros. The city is a character in many fine novels and books. Here, we take a look at some of our favourite work to come out of India’s capital, showcasing various sides of it with a selection of books that have come out in recent decades.

Clear Light Of Day - Anita Desai, 1980

Desai’s novel focuses on the tensions and complex relationships between family members residing in Old Delhi. The novel begins when the characters are adults and progresses backwards into their childhood, set against the tensions of Partition in 1947. Evoking the prose of Chekhov and Arthur Miller, the book embeds the story of the aftermath of partition within the characters’ psyches in a rapidly changing Delhi.

Delhi: A Novel - Khushwant Singh, 1990

"I return to Delhi as I return to my mistress Bhagmati when I have had my fill of whoring in foreign lands." Khushwant Singh’s controversial take on Delhi is vast, erotic, problematic and is considered his magnum opus by many. The narration spans six hundred years, and the narrator is the kind of man we’ve come to associate with Khushwant Singh’s work: a coarse, ageing reprobate with arguably deviant proclivities. He travels through time, space and history to rediscover his city, meeting with poets, princes, sultans, saints, men convicted of treason, temptresses, kings and eunuchs– who have formed the social fabric of Delhi as we know it, endowing the city with its own alluring contradictions and rich history. This book has made readers furious in the past as a lot of the encounters are described from the bedside, and focus on sexual encounters between the narrator and an array of diverse characters. But this psychosexual approach is also often illuminating the city’s hidden desires.

Krishna Sobti - The Heart has its Reasons, 1992

Originally published as Dill-O-Danish in 1992, Sobti’s book follows a love triangle between Bano, Kutumb and Kripanarayan. At the centre is Bano and Kripanarayan’s love affair, that threatens to rupture and pull apart the seams of a family, while Kutumb, the wife, grapples with saving her marriage. Sobti explores the social impact of desire, what makes an outcast in a duty-bound familial hierarchy, arranged marriage defined by socio-economic benefit, and what it means to rebel against diktats. Set in 1920, the story was inspired by Begum Samru ki Kothi, an old, grand mansion in Old Delhi and now the location of an electrical goods market. She transports the reader to a Delhi present only in memory, but not so different from today in some ways – a city of various religions, old money, chauvinism and women persevering despite patriarchal confines of their everyday lives.

An Obedient Father - Akhil Sharma, 2000

Ram Karam, an inspector in the Delhi school system, supports his widowed daughter and eight year old granddaughter by collecting bribes for a small-time political boss. On the eve of Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination, one careless act lays bare a lifetime of violence and the sexual shame behind Ram’s unimpressive public career, involving him in a ridiculous, terrifying political campaign that threatens his life. The book is a stark character study, a portrait of a country afflicted by the horrors of its past, evoking Dostoevsky or Nabokov’s guilt-ridden anti-heroes. It paints a searing picture of what it means to be a civil servant in the capital, of how greed underpins every bureaucratic interaction, of how what is corrupted in the state is also corrupted in the self. Sharma decided to rewrite his own novel 20 years later, but for us, the original was already close to perfection.

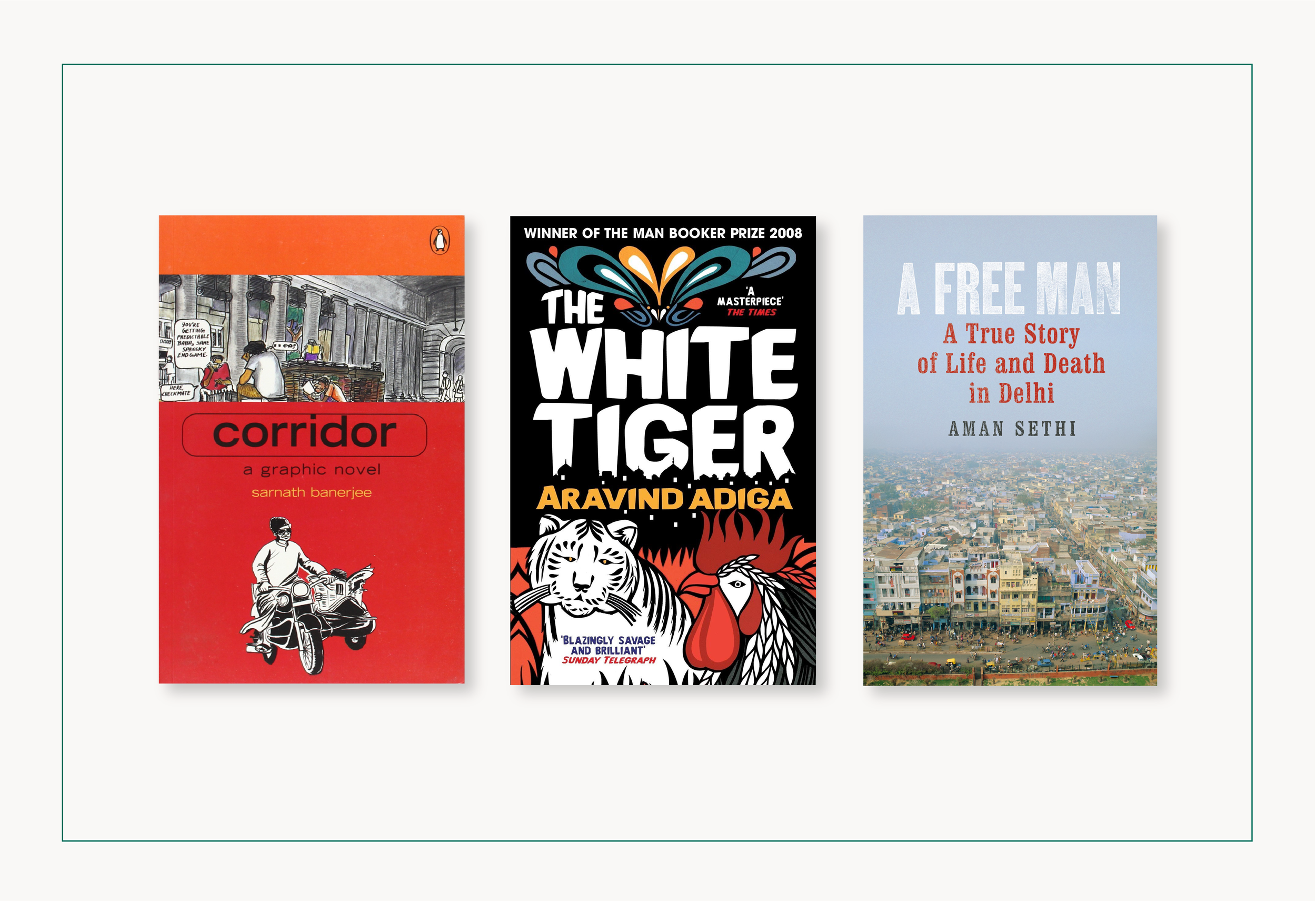

Corridor - Sarnath Banerjee, 2004

This semi-autobiographical graphic novel, has no clear conclusions or story– life continues in the corridors of Delhi. In the heart of Lutyens’ Delhi is Jehangir Rangoonwalla, with his cups of tea and the enlightened wisdom he dispenses along with them, and his second hand books. Among his customers are a postmodern Ibn Batuta looking for obscure collectibles and a love life; Digital Dutta, who lives mostly in his head, torn between Marxian theories and the H1-B visa ; and the newly wed Shintu, who’s looking for the ultimate aphrodisiac in the sordid bylanes of Paharganj. The story takes place between Connaught Place and Calcutta, and the images bring Delhi alive in a unique way.

The White Tiger - Aravind Adiga, 2008

Winner of the Booker Prize and adapted into a film by Ramin Bahrani, this is the story of Balram Halwai’s life as a “self-made” entrepreneur; a rickshaw driver’s son who skillfully climbs India’s social ladder, greased with greed and corruption, to become a chauffeur and later, run a taxi business. He recounts his life in a letter to visiting Chinese official Premier Wen Jiabao, with the goal of educating him about entrepreneurship in India. Balram reflects on the cruelty of the exploitative landlords, under whose reign of terror his destitute family lived in Laxmangarh. There’s resentment and respect, desperation and pity, in the relationships between Balram and his family, between Balram and the other servants, and most ambivalent of all, between Balram and his master. Adiga exposes the socio-economic inequalities that underpin most social bonds in Delhi.

Aman Sethi - A Free Man, 2011

As a young reporter, Aman Sethi, ingratiated himself with a group of labourers at Bara Tooti Chawk. From their storytelling to the character of Mohammed Ashraf, whose journey from butcher to tailor to electrician’s apprentice to destitute labourer in the heart of Old Delhi is fascinating. Sethi falls in with this group of labourer as they talk about leaving behind tempestuous lives back home, doing odd jobs, drinking heavily, going through long spells of unemployment, and dreaming of change. He depicts their existence with pathos and a matter-of-factness, neither judging their stories, nor pretending to be one of them. Delhi comes alive as a character as its fraught relationship with migrants and how it uses and abuses them is made clear, and the city’s chilly indifference to its poorest is laid bare with a deft hand.

Capital - Rana Dasgupta, 2014

Rana Dasgupta’s major nonfiction work is intense, lyrical, clever and a searing portrait of the capital of India. Dasgupta’s narrative bounces between sections of history and his own psycho-sociological profiling of the city’s controversial inhabitants, usually from the upper classes. He posits that Delhi was born out of trauma, and thus uses a certain form of machismo and accumulation of wealth to protect itself from the horrors of the past repeating. While Bombay may be the financial capital of India, Delhi is a city where money equals power which equals everything. Dasgupta paints a vivid picture from 1990s Delhi to now, while shedding light on its tenuous relationship with violence and ideas of masculinity, interviewing industrialists, NGO workers, common people and various others to create a compelling patchwork of a city in flux.

The Association of Small Bombs - Karan Mahajan, 2016

When Tushar and Nakul Khurana, two Delhi schoolboys, go to pick up their family’s television set at a repair shop with their friend Mansoor Ahmed one day in 1996, a series of “small” bombs detonate in the Delhi marketplace. The boys lose their lives and Mansoor survives, suffering both physical and psychological trauma. The novel’s narrative ripples out from this point on, moving back and forth in time, examining the grief that engulfes the parents of the dead boys, the trauma of the survivors and the damaged, disenfranchised lives of the terrorists who executed the attack. The Khuranas are members of the left liberal class and the grief warps their lives; sending them into weird tangents, and their politics lurch to the right as they’re hailed by the media as icons of loss. Mansoor, as he wanders through the streets of Delhi in a fugue state of disassociation, isn’t granted the same dignity of mourning. The terrorists are inconspicuous men; concerned more with how they have to steal a car to plant the bomb, than committing actual mass murder. The prose is of an elevated realism that focuses on the vicissitudes of the aftermath of the bombing.

The Windfall by Diksha Basu, 2017

The Windfall is mainly about Mr. and Mrs. Jha, whose son is in America dealing with slipping grades and romantic entanglements while their marriage is in the doldrums. Having to deal with gossipy neighbourhood aunties, cramped spaces and the daily dramas of stolen yoga pants and failing marriages, they seem like a typical East Delhi family. But then Mr. Jha comes into a large sum of money unexpectedly, moving them to the posher part of town where he’s concerned with showcasing status - tailored suits, hired security, shoe polishing machine et al, until he’s forced to reckon with what really matters. A social satire, the whole point of Jha’s wealth lies in its exhibitionism, as anybody who’s spent time in Delhi would know.

Djinn Patrol On The Purple Line by Deepa Anappara, 2020

Deepa Anappara’s debut novel captures innocence and the consequent loss of it, friendship and the impact it has in an increasingly divisive world, disaffection without any of the glamour or pathos, painting a brilliant, often caustic but always deft picture of growing up in a slum in an unnamed Indian city that seems suspiciously like Delhi. Her unsentimental description of the smog, the lurking men in the shadows, the uncaring employers of children at tea stalls, the spirits of women once stationed at red lights, the drunkard father, the father trying to do better despite his circumstances and the endless shitshow of Indian bureaucracy, shines through in the voice of 9-year-old Jai, a narrator inspired by shows like Police Patrol to go on a ‘detectiving’ adventure with his best friends, Pari and Faiz. Local goons populate his government school where the brightest part of the day for Jai and his friends is their mid-day meal (often just watery gruel). The sweet Muslim Chacha who employs Faiz at his shop is the first suspect in the string of disappearances that stain the daily life of the basti, a hi-fi madame in a hi-fi building might be tangentially involved in the disappearances and the police can’t wait to wash off their hands of a people that have been relegated to the outskirts of a bustling city. The novel shifts perspective often and inhabits the experiences of the disappeared children-- bringing us face to face with the danger they navigate in simply going and coming back from school. No fancy drivers to pick them, no State buses even to hitch a ride back on. Deepa’s book is truly about India’s deliberately forgotten and her gaze is one of wonder, curiosity, playfulness and grit - a unique take on one of Delhi’s most grisly serial killers that surprises in myriad ways.