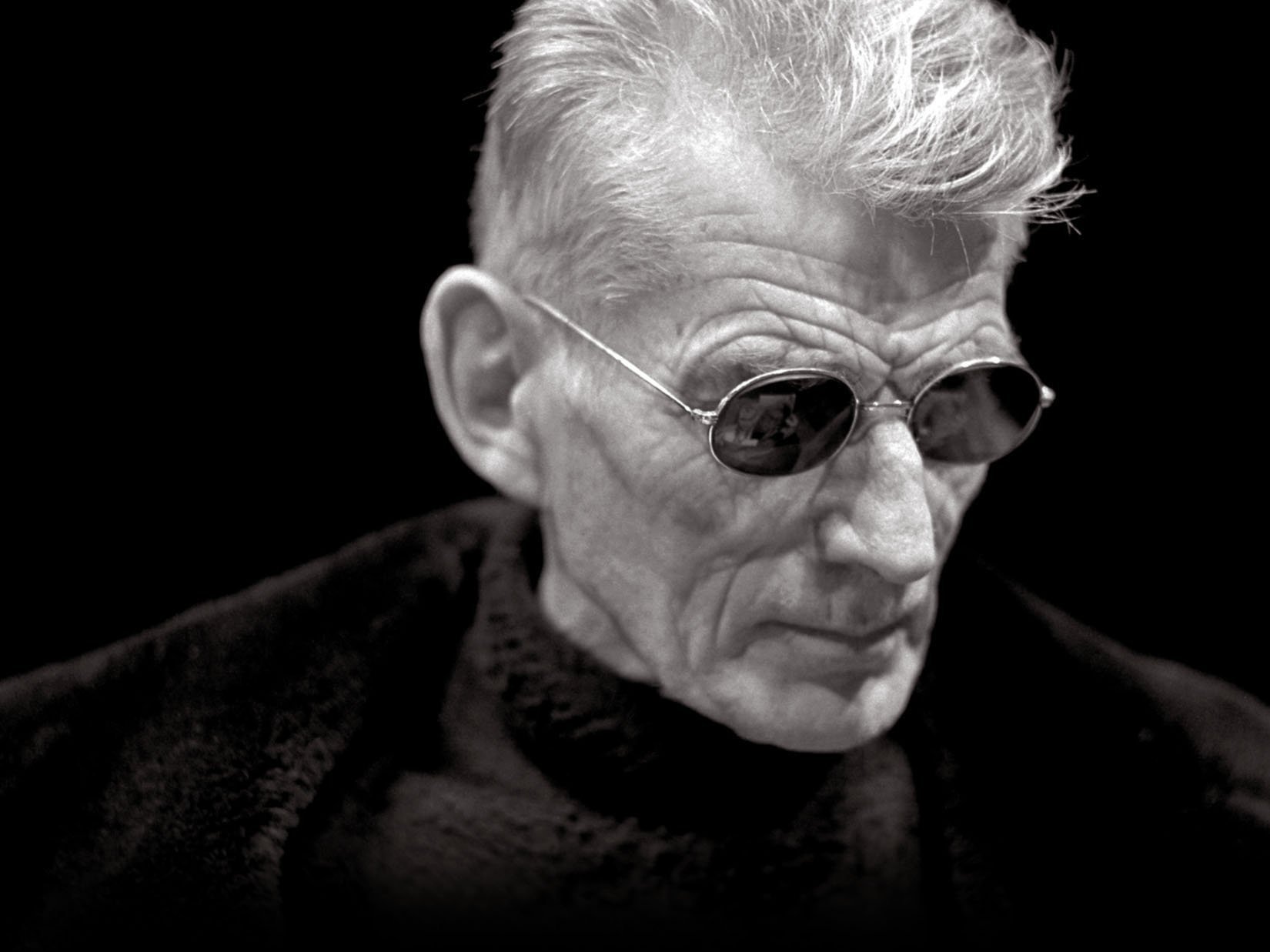

Part of the Process: Samuel Beckett

Part of the Process is a series in which we chronicle the often turbulent, usually absurd and always interesting lives of authors we admire. It’s not easy to be a writer in the 21st century, but in a strange way, reading about the trials and tribulations of those who seem to have ‘made it’ can be a reminder that it has always been a difficult process.

*

Although he is now known as one of the greatest Irish writers of all time and one of the most influential modernist writers, Samuel Beckett’s journey to the kind of hallowed legacy he enjoys was an often bizarre one. Beckett played many roles in his lifetime, from novelist to poet to playwright to translator, and wrote in both English and French. But his journey as an artist was fraught and began with failure.

Beckett was born in 1906 in a suburb of Dublin, to a fairly wealthy family. In 1923 he entered Trinity College Dublin, where he studied modern literature and Romance languages. A natural athlete, he excelled at cricket as a left-handed batsman and a pace bowler. Later, he played for Dublin University and played two first-class games against Northamptonshire. As a result, he is the only Nobel literature laureate to have played first-class cricket and feature in the Wisden Almanac.

After graduating, he taught briefly at a college in Belfast, then took up the post of lecteur d'anglais at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris from 1928 to 1930. While there, he was introduced to renowned Irish author James Joyce by a poet and close confidant. This meeting had a profound effect on Beckett, who assisted Joyce in various ways, one of which was research towards the book that became Finnegan’s Wake. Beckett worked on his own writing concurrently, but his work was too influenced by Joyce and didn’t see much success.

His first novel, ‘Dream of Fair to Middling Women’, wasn’t picked up by any publishers, and the book of short stories he salvaged from it, ‘More Pricks than Kicks’, came out in 1934 but sold disastrously. The collection follows a mirror image of Beckett around Dublin on a series of misadventures and sexual escapades, but has been called a ‘challenging and frustrating read’. As the second World War approached, Beckett traveled through Europe, particularly Germany, where he studied artworks that rebelled against the Nazi party. He also underwent psychoanalysis, wrote poetry and a book on Proust and returned to France, where he settled for a while.

In January 1938 in Paris, Beckett was stabbed in the chest and nearly killed when he refused the solicitations of a notorious pimp (who went by the name of Prudent). Joyce arranged a private room for Beckett at a hospital. The publicity around the stabbing attracted the attention of Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, who knew Beckett from his first stay in Paris. Their encounter led to a relationship, which would become a lifelong companionship. Beckett eventually dropped the charges against his attacker—partially to avoid further formalities, partly because he found Prudent likeable and well-mannered after an apology.

After the Nazi occupation of France in 1940, Beckett joined the French Resistance, in which he worked as a courier. On several occasions over the next two years he was nearly caught by the Gestapo. In August 1942, his unit was betrayed and he and Suzanne fled south on foot to the safety of the small village of Roussillon. During the two years that Beckett stayed in Roussillon he indirectly helped sabotage the German army in the mountains, though he rarely spoke about his wartime work in later life. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille de la Résistance by the French government for his efforts in fighting the German occupation, but apparently Beckett himself would refer to the work with the French Resistance as "boy scout stuff".

Although Beckett had written some poetry in French before the war, it was in its aftermath he resolved to commit fully to the language, “because in French it is easier to write without style”. This decision, and his switch to the first-person voice, resulted in one of the most notable artistic transformations in 20th-century literature. His exhaustingly self-conscious early manner gave way to a new form that was modernist, rejecting the influence of Joyce and others and instead attempting to go in the opposite direction - to reject realism in favour of the absurd, describing strange journeys and tortured psyches in stories he wrote after the war.

After a collection of stories that describe the descent of their unnamed narrators (possibly the same man) from bourgeois respectability into homelessness and death, as well as plays that slowly became popular both in France and other places, Beckett divided critical opinion. Some early philosophical critics including Sartre praised him for his revelation of absurdity and his critical refusal of simplicities, while others condemned him for nonsense writing and a 'decadent' lack of realism. Beckett came to believe failure was an essential part of any artist’s work, even as it remained their responsibility to try to succeed.

Between the late 1940s and the 1950s, Beckett produced a great deal of work in French, and usually translated his own work to English as well. From Molloy to Malone to Waiting for Godot, probably his most famous work, he gained recognition and a reputation across Europe. Suzanne, his lifelong companion, was critical to the success of his work, pitching it to publishers and in the theater and acting as an agent of sorts. During the 1950s, Beckett became one of several adults who sometimes drove local children to school; one such child was André Roussimoff, who would later become a famous professional wrestler under the name André the Giant. They had a surprising amount of common ground and bonded over their love of cricket, with Roussimoff later recalling that the two hardly talked about anything else.

In the early sixties, Beckett and Suzanne married in a secret ceremony in England, which was kept under wraps because of something to do with French inheritance law. The success of his plays led to invitations to be a theater director in various parts of the world, though he largely settled between England and France. From the late 1950s until his death, Beckett had a relationship with Barbara Bray, a widow who worked as a script editor for the BBC. The encounter between them when Beckett came to work on a production was significant, for it represented the beginning of a relationship that was to last, in parallel with his marriage to Suzanne, for the rest of his life.

In October 1969, while on holiday in Tunis with Suzanne, Beckett heard that he had won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Anticipating that her intensely private husband would be saddled with fame from that moment on, Suzanne called the award a "catastrophe". While Beckett did not devote much time to interviews, he sometimes met artists, scholars, and admirers who sought him out in the anonymous lobby of the Hotel PLM Saint-Jacques in Paris – where he gave his appointments and was known to be warm and happy to discuss his work. But he had a stark opposition to other forms of publicity and stayed increasingly in the confines of his Montparnasse home.

Beckett’s work after the 1960s is sometimes considered ‘minimalist’, as he tended increasingly towards modernism, rejecting the ‘external trappings of existence, the accidental and superficial aspects that mask the basic problems and the basic anguish of the human condition’. Much of his work uses absurdity to try and come to terms with the fact that we have been thrown into the world, into being, without knowing the true nature of our selves.

In the late 1980s, Beckett suffered from ill health, including emphysema and suspected Parkinson’s disease. Suzanne died in July 1989, and Beckett spent his last few months in a nursing home before passing in December of that year. The two are interred together at Montparnasse cemetery in Paris, sharing a simple granite gravestone that followed Beckett’s demand: it should be ‘any colour, as long as it is grey”.

There are entire books and papers on Beckett’s legacy, on the vagaries of his life, his wartime experiences and the evolution of his work. There is far more to explore, but hopefully this selection of incidents makes it clear is that his was a meandering journey which produced work which has continued to be relevant in various forms up to this day.